Anna Natalia Malachowskaja is a well-known Soviet and Russian author, feminist, and dissident. In 1979, together with Tatiana Goricheva, Tatiana Mamonova, and Julia Voznesenskaya, she wrote and edited a feminist samizdat publication Женщина и Россия [Woman and Russia] and later Maria. These publications were deemed anti-Soviet; the women were questioned by the KGB and forced to emigrate. Having settled in Austria, Malachowskaja completed her Ph.D. at the University of Salzburg. She turned her research into the Russian folklore character of Baba Yaga into a series of published books where she argues that the fairy tale character is a marginalization and amalgamation of three goddesses of the ancient world. In addition to her scholarship, Malachowskaja is the author of novels, collections of stories, and poems. Malachowskaja’s fiction is frequently accompanied by art. As an artist, she has exhibited her work in St. Petersburg, Vienna, and Salzburg.

Continue reading “Ugrinovich and the Sex Giant: Fiction by Anna Natalia Malachowskaja, translated by Anastasia Savenko-Moore”Tag: feminism

The Everyday and Invisible Histories of Women: A Review of Oksana Zabuzhko’s Your Ad Could Go Here by Emma Pratt

We at Punctured Lines are grateful to Emma Pratt for her review of Oksana Zabuzhko’s Your Ad Could Go Here (trans. Nina Murray and others). This review was planned before the war broke out and was delayed, among other things, by my inability to focus on much when it did. I am thankful to Emma for her patience with this process and for bringing Zabuzhko’s work to the attention of our readers. Please donate here to support Ukrainian translators and here to support evacuation and relief efforts.

Continue reading “The Everyday and Invisible Histories of Women: A Review of Oksana Zabuzhko’s Your Ad Could Go Here by Emma Pratt”Secrets: An Excerpt from Nataliya Meshchaninova’s Stories of a Life, translated by Fiona Bell

Nataliya Meshchaninova is Russian filmmaker. In 2017, she published a book of autobiographical short stories that resonated with her audience, in part, because they supported the Russian #metoo movement. In February 2022, Deep Vellum brought out Fiona Bell’s translation of Meshchaninova’s book under the title Stories of a Life. We are honored to share with you an excerpt from this book, a section from the fourth chapter, “Secrets.”

Virtual Conference on Radiant Maternity in Literature and Culture

As readers, feminists, and ourselves parents, we at Punctured Lines are happy to learn that Drs. Muireann Maguire and Eglė Kačkutė are organizing a two-day conference to launch the Slavic and East European Maternal Studies Network. The conference is to take place on January 28 and 29, 2022, and the stellar list of presenters and topics includes our contributor Natalya Sukhonos’s paper on Motherhood, Math, and Posthumous Creativity in Lara Vapnyar’s Russian-American novel Divide Me by Zero. We ran a Q&A with Lara Vapnyar shortly upon the publication of that novel.

Our contributor Svetlana Satchkova will participate in an online discussion on Motherhood, Gender, Translation and Censorship in Eastern European Women’s Writing, and scholar and translator Muireann Maguire will present a paper on Breastfeeding and Female Agency in the Nineteenth-Century Russian Novel.

The full listing of events is available on the conference’s website. To register, please email SEEMSmaternal @ exeter.ac.uk by January 21st, 2022. The sessions will be conducted in English.

Born in the USSR, Raised in California: Video Recording

Thanks to everyone who could attend our event on Saturday, December 4th, and thank you all for your engagement and for your wonderful questions. For those of you who couldn’t make it, here’s the video recording from the event and links to our work.

Seven immigrant writers read their fiction and nonfiction related to immigration, identity, family history and the mother tongue(s). Let’s talk about buckwheat and pickled herring with beets. What do you do if your children refuse to eat traditional foods? Or when your dying grandmother forgets English and Russian and begins speaking to you in Yiddish? Does a Soviet-era secret still matter when the country no longer exists? We explore love, life, loss and the nuances of living with a hybrid identity.

Continue reading “Born in the USSR, Raised in California: Video Recording”Pocket Samovar: Interview with Konstantin Kulakov, Founding Editor, by Alex Karsavin

Today Punctured Lines is delighted to feature Alex Karsavin‘s interview with Konstantin Kulakov, Founding Editor of Pocket Samovar, “an international literary magazine dedicated to underrepresented post-Soviet writing, art & diaspora.” A huge thank you to Alex for the initiative to do this interview for the blog and to both Alex and Konstantin for their work on this piece. An equally huge thank you to the editors of Pocket Samovar for creating a space for post-/ex-Soviet writers. Submission guidelines can be found here.

Alex Karsavin: Can you briefly give me the origin story of Pocket Samovar? How did a project that began as a localized conversation between two students at Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School end up involving so many international actors? How did you go about establishing these lines of communication? And finally: how has Pocket Samovar been able to, in a remarkably short spate of time, reach such a dispersed and disparate audience?

Konstantin Kulakov: It started in fall 2019, in Boulder, Colorado at the Jack Kerouac School. It was Kate Shylo, who’s from Yalta, Crimea, me from Russia, and Ryan Onders, who’s from Ohio. Late in the summer, Ryan and I struck a relationship over poetry performance, especially our obsession with Yevtushenko and the orality of Soviet poetry. Shortly, the three of us got together over borscht and spoke about a magazine dedicated specifically to diasporic communities. At first, the word we used was “Eurasia.” Later we realized that “post-Soviet” would be a more accurate term, and we brought it up to Jeffrey Pethybridge, who connected us with Matvei Yankelevich. Matvei was brilliant; he put us in contact with Boris Dralyuk and Eugene Ostashevsky, which ultimately led to the establishment of an advisory board. We didn’t just want this to be a trendy journal that’s translating East European writing. We wanted to highlight underrepresented writers of the post-Soviet space: queer, LGBTQ, Muslim, writers of color, including writers from Transcaucasia, Central Asia, and so on. The hardest part, of course, was to establish these links across time zones, languages, and cultures. Our advisory board proved extremely useful in finding people like Paata Shamugia and Hamid Ismailov. I myself found people like Evgeniy Abdullaev, whose pen-name is Suhbat Aflatuni; he’s based out of Tashkent. It is important to emphasize, for us, the diasporic part of our mission does not center writers in the west; instead, the magazine aspires to be rhizomatic, bridging the gap between North American and Eurasian literary communities.

Alex Karsavin: I was struck by the claim on your site that Pocket Samovar was influenced but not necessarily determined by its editors’ relationship to “Soviet cultural memory.” This is a very rich and arguably fraught territory. Before we go into the particulars, would you mind delving into your (or your colleagues’) relationship to the region at large (be it personal, literary, or academic)?

Konstantin Kulakov: I can only confidently speak for myself. I left Russia when I was 10 years old: a kind of identity rupture or separation at a formative time. And that longing for homeland is really what it’s about for me. The only way I could connect to Russian contemporary literature was online or books. And there was something missing in that, like: Oh, here’s a poem. Here’s an anthology of contemporary Russian poetry by Dalkey Archive Press. And that’s it. I opened the book, and I never felt that it offered me an opportunity to improve my Russian, or to meet Russian people. (Before the pandemic hit we had hopes of actually having events and things of that nature.) So for Kate and me, it really was founded around diasporic longing for a connection to the post-Soviet space, and specifically the kind of literary culture where people can stand up and recite a poem by heart. Living and going to school in Russia as a kid, I hated recitation, because it was required and I wasn’t good at it. In my early childhood, I was moved between Russia, England, and America. I was bilingual and confused, often wonderstruck by language, and maybe that’s why I’m a poet. In many ways, for me, editing this magazine is a return to the language at a time when I feel ready to appreciate it. In Kate’s case, she was born in Yalta and also traveled; she has this nomadic sensibility. I think what interested her was the emphasis on publishing underrepresented voices (particularly feminist and queer). Ryan, of course, came to us via Yevtushenko and translation.

Alex Karsavin: Could you say a bit more about your personal relationship to Soviet cultural memory specifically (given the prominent role it plays in the site’s call for submissions)?

Konstantin Kulakov: Soviet cultural memory. Hmm. I mean, I was born in 1989 in Zaoksky, a town outside of Moscow.

Alex Karsavin: Right at the tipping point …

Konstantin Kulakov: Yeah. I entered a world of collapse, in a state of flux. My memory of that time is mostly of things falling apart and being built up. I actually grew up during the construction of the first Protestant seminary co-founded by my father. So there’s this idea of: “Look! Democracy, religious liberty, international dialogue, etc. are finally coming to Russia!” But at the same time, having been in the United States for 20 years (I’m 31), having experienced individualistic consumerism, there’s now this longing for the samovar, for the communal aspect of poetic memorization and recitation, a longing for something as immense as the stadium poetry of Yevtushenko and Bella Akhmadulina. The longing was also in part a reaction to this feeling among some exiles that Russia is authoritarian, that the arts are neglected or backwards, etc. And something in me always knew the latter was false. I thought: “I know there are poets in Russia and all over the post-Soviet space.”

Alex Karsavin: Why Pocket Samovar for the title? To my mind, the samovar draws obvious connotations to the Tsarist Empire, and nationalism more broadly. Yet, and correct me if I’m off mark, there seems to be a dislocation happening here (even in the simple reimagining of this bulky static object as something miniature and mobile). Am I wrong to interpret this as a sort of queering?

Konstantin Kulakov: There are some things to unpack here. In fact, the mission statement used to be a history of the samovar. It actually emerged in Azerbaijan. The samovar finds archeological origin in the tea drinking devices of Azerbaijan, not Russia. So we were not trying to center the Russian space but rather the region as a whole, its complex, boundary-crossing geography and culture. The communal aspect is also very important. The samovar is circular and presents a spatial situation that is meant to be enjoyed among friends, conversing as equals in a non-hierarchical, free, and spontaneous manner. In the end, we’re trying to be more like a tea room than just a competitive journal that publishes the best of post-Soviet writing. So, if the samovar, something bulky, fits in the pocket, you can definitely say this is a queering; in many ways, the situation of the diasporic writer demands an understanding of fluidity. For us, national identity can change overnight, and language, when queered, affords that fluidity.

Alex Karsavin: Pocket Samovar appears to be the newest in a series of recent publications which take this particular region as their focus (Mumber Mag, Alephi, to some degree Homintern). The magazine is unique, however, in its attempt to put the stateside literary diaspora in communication with its FSU (former Soviet Union — PL) roots. Why is this emphasis on dialogue so important for Pocket Samovar? How does it relate to the magazine’s stated desire (to paraphrase Madina Tlostanova) to reimagine the post-Soviet condition not as a lamentation of lost paradise, but as a way to re-existence?

Konstantin Kulakov: We emerged in Boulder, Colorado, although we are expanding now. One of our editors is in Brooklyn; I might be moving to Brooklyn soon, actually. And then two of our editors are based in Europe, specifically in Luxembourg and in Basel, Switzerland. Daily operation and editorial decisions present new limits and opportunities. So the idea behind Tlostanova’s quote is that we’ve already opened Pandora’s box, so to speak. We can’t go back. Globalization is everywhere. And I think the name “pocket samovar” speaks to that question very concretely. Being in this globalized, fast-paced world, everything is now pocket-sized, everything is mobile, it’s almost like you have to be that way to survive. Ryan Onders, our managing editor, asked me one day: How would the magazine exist physically as a print edition? And I said: It’s a diasporic thing. It’s nomadic. So it has to fit in the pocket, right? That’s when I realized it had to be Pocket Samovar.

The thing is, we can’t go back in time, nor can we escape the Soviet legacy. The “re-existence” Tlostanova speaks of is the ability to create something new and necessary, something that’s based around community in an individualistic and competitive globalized world. For this reason, our new issue emphasized the virtual tea room recordings (of which Stanislava Mogileva‘s was my favorite). We strategically decided to put the video at the top of the page to make it central, and the text secondary. So when you click the link and open the video, there’s this feeling that we’re still honoring that tradition of orality and community, a re-existence of sorts.

Alex Karsavin: Perhaps it’s too early to tell, but what kind of international reception has Pocket Samovar had so far? Also, I want to dive a little deeper into the question of inter-scene dialogue. Given that your contributors represent such disparate literary (and feminist) movements, what kind of exchange (intellectual or affective) have you noticed cropping up in your virtual tea room? Do you think the formal arsenal and thematic concerns of the writers featured in the first issue coalesce into some sort of recognizable whole? Particularly I’m interested in the way writers deal with the theme of dislocation (for example, Stanislava Mogileva appears to recoup the folk song and oral epic genre in the service of Russian feminism, while Elena Georgievskaya queers the biblical language of Revelation).

Konstantin Kulakov: It’s interesting. International communication is definitely happening, even as we speak, on social media. That’s where I’m seeing it and I can’t really talk about the nature of the dialogue yet because we first need to have more events. But it’s generally a sense of excitement that I’m seeing. To borrow a term from Durkheim, it was something of a collective effervescence, albeit virtual. At first, there was this fear among the editors that in calling ourselves post-Soviet, people would freak out and not want to be affiliated with that authoritarian, violent legacy to which we all have our own complicated relationship. However, I think the nature of the post-Soviet space is integrated in such weird ways that there is always literal and discursive travel occurring between the various republics and Russia. For example, Evgeniy Abdullaev is based in Tashkent and has a manifesto called “Tashkent Poets,” but he writes in Russian (not dissimilar to the Soviet-era poet, Bulat Okudzhava, who was of Georgian and Armenian descent). So there’s always this traversing of borders going on. In terms of the response to Pocket Samovar (going off the website traffic), it’s clear that it went completely international. It hit every continent. Because some of the contributors shared it in Azerbaijan, it ended up going all over Central Asia, Transcaucasia, and even to parts of the Middle East, like Afghanistan and Iraq. That, to me, was really encouraging.

It is important to emphasize how literature of the post-Soviet space and literature of the post-Soviet diaspora define the issue. In regards to writing from the region, I would like to highlight Stanislava Mogileva, Elena Georgievskya, Vitaliy Yukhimenko. They are all queer/non-binary poets. Although they have differences, they are united by the similar role sociality, orality, and free verse plays in their work. Learning from these writers and movements–through their work, talks, essays, interviews– is exactly what future issues of Pocket Samovar will be devoted to.

The post-Soviet diasporic writer, on the other hand, finds themselves in a contrasting position to homeland. The post-Soviet diasporic writer may reject their homeland, share an ambivalent attitude to it, adopt a hyphenated identity, or alternate between all of these. Alina Stefanescu’s poetry definitely does not shy away from the brutality of the Soviet experience, but nor does she reject it. “Pickled Plums” celebrates familial traditions illustrating how a planted sapling or thimble of tuica can impart her diasporic life with a sense of safety or vitality of speech. Anatoly Molotkov’s “Poison in the DNA” is aware of the powerful role of the past, but the speaker firmly resists identification with his Russian roots because the roots are “rotten.” However, after reading his poem, “Letting the Past In,” we see Molotkov’s more positive kinship to another Soviet artist: Andrei Tarkovsky. Nonetheless, given the complexities of nationality, our magazine conceives of diaspora very broadly. For example, Steve Nickman’s poetry concerns itself not with land, but with the lives of post-Soviets in the United States. It is too soon to tell, but I can only expect that such literary encounters will continue to demonstrate the need for further exchange and connection, especially given the global challenges we face.

Alex Karsavin: What’s the long-term vision for the magazine?

Konstantin Kulakov: We eventually want to turn the magazine into a nonprofit similar in format to that of Brooklyn Poets. We of course want to grow in funding. We imagine ourselves as a platform for the diasporic community that features poetry and translation workshops, reading events, and conferences. We want to serve as our own social platform, where poets can comment on each other’s published poems. We want to optimize interaction and user experience. The fact is that everything nowadays is becoming more mobile; for example, 60% of the people visiting the website are using phones. At the same time, we don’t want to lose the physicality of a print magazine, of literary evenings (to use a Russian term), which is why our current emphasis is on raising funds for the print issue.

Konstantin Kulakov is a Russian-American poet, educator, and translator born in Zaoksky, former Soviet Union. His debut chapbook, Excavating the Sky, was published by Dialogue Foundation Books (2015). Kulakov is the recipient of the Greg Grummer Poetry Award judged by Brian Teare and holds a Master of Divinity degree from Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York. His poems and translations have appeared in Spillway, Phoebe, Harvard Journal of African American Policy, and Loch Raven Review, among others. He is currently an MFA candidate at Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School in Boulder, Colorado and co-founding editor of Pocket Samovar magazine.

Alex Karsavin is a Russian-American literary translator, with translations and writing published in the F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry anthology, PEN America, Columbia Journal, New Inquiry, Sreda, and HOMINTERN magazine. Ilya Danishevsky’s hybrid prose-poetry novel Mannelig v tsepyakh (Mannelig in Chains) forms Alex’s main translation project, a collaboration with veteran Russian-English translator Anne Fisher, funded by the University of Exeter’s RusTrans project. They are currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures at UIUC. They are a 2020 ALTA travel fellow.

Feminist and Queer Russophone Poetry

This year, English-speaking readers will be introduced to three books in translation from Russian, each of which is groundbreaking on its own terms; taken together, these books showcase the aesthetic potential of feminism in contemporary Russian-language poetry. The feminist and queer voices in these books are amplified by the group of poet-translators, whose own politics and identities allow them to negotiate the cultural gap between russophone and anglophone contexts, enriching both. Punctured Lines is proud to introduce the three books and our conversation with Ainsley Morse, Eugene Ostashevsky, and Joan Brooks, who as editors and translators served to bring these books to English-language readers.

Update: This post was originally published on October 14, 2020. Subsequently, Joan Brooks asked us to remove their answers to the questionnaire, and we’ve done so on December 11, 2020.

The Books

Lida Yusupova’s collection, The Scar We Know, edited by Ainsley Morse, with translations by Madeline Kinkel, Hilah Kohen, Ainsley Morse, Bela Shayevich, Sibelan Forrester, Martha Kelly, Brendan Kiernan, Joseph Schlegel and Stephanie Sandler

(Cicada Press, Winter 2020/21)

F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry, an anthology edited by Galina Rymbu, Eugene Ostashevsky and Ainsley Morse, with original poems by Lolita Agamalova, Oksana Vasyakina, Elena Georgievskaya, Egana Dzhabbarova, Nastya Denisova, Elena Kostyleva, Stanislava Mogileva, Yulia Podlubnova, Galina Rymbu, Daria Serenko, Ekaterina Simonova and Lida Yusupova; translated by Eugene Ostashevsky, Ainsley Morse, Helena Kernan, Kit Eginton, Alex Karsavin, Kevin M. F. Platt, and Valzhyna Mort

(isolarii, October 2020)

Galina Rymbu’s collection, Life in Space, translated by Joan Brooks with an introduction by Eugene Ostashevsky and contributions by other translators

(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020)

NB: Dear readers, please pre-order and buy these books and request that your local libraries purchase them for their collections. This directly supports the work of everyone involved in their making.

Conversation

PL: These are Rymbu’s and Yusupova’s first poetry collections in English, and many authors in the anthology are being published in English for the first time. How did these books come to be? What’s the story–or stories–behind their near simultaneous publication in the US?

Ainsley Morse: I met Yusupova in 2017, when we invited her as the “poetic guest” to AATSEEL (the annual conference of the Association of American Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages)–when funds allow, we like to invite a poet to have translators workshop some of their poems and to give a reading. The idea of making a book started then but really took shape as, over the ensuing couple of years, I kept encountering other translators who were interested in Lida’s work and wanted to take on various texts. (I am the editor of the book and did some of the translations, but really couldn’t have done this project on my own.) Most of the other books I’ve done have been labors of love–me wanting to bring something strange that I love into English, but not always with a huge resonance–but my sense of Yusupova’s book is that it almost made itself; it sensed its English-language audience ready and waiting.

Eugene Ostashevsky: It’s both a coincidence and not a coincidence. Historically, it’s not a coincidence. It has to do with the emergence of feminist and queer poetry in Russia in this decade, mostly written by the young poetry generation, i.e. by people who did not live in the USSR. Yusupova, who is older and did live in the USSR, was the inspiration for some of this poetry. Rymbu is currently its most visible representative. I first came across a poem of hers by chance, online: it was during Maidan, in February 2014. It was the Lesbia poem, about the coming of fascism to Russia. It was obviously the work of somebody who had a vast poetic erudition but was doing something new with it, and something wildly compelling. So I did a feature on her in Music and Literature with Joan’s translations. Sebastian and India, the publishers of isolarii, read the feature and contacted me. We decided to do an anthology that she would edit and that would represent some of the people from her circle. It just so happened that all three books–the anthology and Rymbu’s and Yusupova’s English-language books–are coming out simultaneously. I think we have COVID to thank for it, because they all got held up by the lockdown in different ways.

PL: There have been a number of writers in the russophone space who wrote to queer and feminist themes in the past, including Yusupova herself, who published her first collection in 1995. In 2017, a collective of poet-activists launched “Ф-Письмо [F-Writing],” an online platform, specifically dedicated to feminist poetry. F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry gathers the work of poets associated with the F-Writing collective who intentionally blur the lines between poetry and activism. They do this both by breaching taboo topics–for instance, the physiology of the female body (as in Galina Rymbu’s recently published poem “My Vagina”)–as well as by breaking with tradition in Russian-language poetry by moving away from rhyme and meter. What do you see as some of the most exciting and innovative aspects of the poems you worked with?

Ainsley Morse: A noticeable shift away from rhyme and meter has been underway in Russian poetry for at least twenty years now, probably more like thirty (depending on how you understand “noticeable”). But this shift has had a political charge, since it certainly coincided with other, more noticeable rapprochements with the West, and to this day the majority of Russians would certainly tell you that poetry is something that rhymes. Some of the poets in the anthology, particularly the ones with personal experience of life in the USSR–Ekaterina Simonova, or Elena Georgievskaya, for instance–started out writing much more traditional-sounding verse. Lida Yusupova (b. 1963) certainly grew up in a poetic environment dominated by rhyme and meter, but her years of living (and reading) abroad have also surely affected her general sense of poetry. In any case, when she gives specific instructions to translators / editors to “let the lines run on as long as the page will let them”–you know this is someone who has a sense of the constrictions imposed by a neat stanza, such that these unhinged rambling lines are a really meaningful part of her poetics. I’d say, though, that most of the poets represented in the anthology came of age as poets in an (admittedly rarefied) environment that saw free-verse as the new normal; as Eugene describes, their innovations are happening more in the realm of selfhood, subjectivity, identity.

Eugene Ostashevsky: Feminist and queer work–and left-wing political work in general–is what’s exciting in Russian poetry now, at least as far as movements are concerned. Russian poetry has for many generations generally tended to avoid politics. There were a number of deep reasons for it, from the cultural policy of the state to ideologies about poetry held even by people who were deeply anti-establishment. Of course, the aim of the state was to knock out the political instinct altogether, or rather the critical political instinct, to make people believe that politics is corrupt, so that conformism may rule. (This is still the current strategy because it works.) At the same time, stylistic experimentation sufficed to demonstrate your anti-establishment colors, because stylistically interesting work generally could not be published under the Soviets. In the aughts, during Putin’s first decade, some poetry started to break away from the general aversion to political engagement. And it was also a poetry that started breaking other taboos–including talking about the body, and about sexuality in ways that ultimately turned out to be socially impermissible and politically volatile. This poetry moved towards reflecting upon the self in new ways, towards constructing the self differently, and that self would very obviously no longer be a Soviet self, and not even a post-Soviet self. So it was anthropologically innovative, which made it politically innovative also.

However, it was the state that took the crucial step of making such poetry necessarily and obviously political. The state politicized sexuality by associating LGBTQ+ issues with the decadent West, pretending that LGBTQ+ posed a danger to Russian society, as if they were some sort of rainbow-colored NATO special forces, largely criminalizing them and positioning itself as the defender of family values. Once that happened–once Putin, as dictators everywhere, consciously threw in his lot with defense of patriarchy–feminist and queer poetry automatically got shoved onto the political frontline, and automatically became–it’s perhaps unsuitable to use military metaphors here but in Russia we/they like military metaphors–the vanguard of resistance to Putin or the putative Putin or the state.

PL: Most of the poets included in the three books are closely connected to each other by personal and artistic ties. F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry was edited and includes work by Galina Rymbu as well as Lida Yusupova’s poetry. What connections between the three books strike you as the most meaningful?

Ainsley Morse: As someone who teaches / tries to teach Russian poetry to American undergraduates, I love that these books are coming out in hot succession–it’s a rare moment when the slow and painstaking world of translation publishing comes a little closer to the pace of the “real life” of this subset of Russian poetry, where these poets are all constantly releasing work that is in conversation with, responding to, each other. Single-author books always give a broader and deeper sense of a writer than a couple of poems in an anthology, but here we also have this anthology providing a whole additional level of context to both Rymbu’s and Yusupova’s work; I would hope, too, that readers intrigued by some of the anthology authors might feel empowered to suggest further translations of some of them. Another rare treat (pedagogical and otherwise) is the possibility, at least with the anthology and Yusupova’s solo book, to compare the voices of different translators grappling with the same poet’s work. I’m also excited and curious about the way English-language readers will react to all three of them being available at once: it seems like an unusual opportunity for a more in-depth and nuanced cross-cultural poetic dialogue, more or less in real time.

Eugene Ostashevsky: Well, it’s the same corpus. Poems don’t really get written individually. They are always collaborations. When you’re a loner, you collaborate with dead people. But here you have work by contemporaries responding to each other–you have a conversation of the living, who are trying to make sense of themselves and of their surroundings. The F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry anthology has an incredible poem by Oksana Vasyakina, “These People Didn’t Know My Father,” which starts by talking about the importance of Yusupova as a catalyst. For me, I love Galya Rymbu’s slightly earlier, more anthemic poems in White Bread, that Joan translated, and it’s really interesting to see her return to the same area in “My Vagina” but years later, as a different person. But she works in a number of different directions, and another direction picks up, for example, on the poetics of Arkadii Dragomoshchenko, a Petersburg poet of an older generation, who died a decade ago, and a lot of whose images are apophatic, nonvisualizable.

PL: Despite their similarities, these are three very distinct books, published by three separate presses and presumably aimed at different, albeit partially overlapping audiences. What are some of the unique aspects of each of these books?

Ainsley Morse: As I said earlier, I really have this sense that the Yusupova book “made itself”–I don’t ever remember having a serious conversation about the contents, it just came together in what now feels like a strikingly harmonious and well-balanced structure. All the texts were proposed by the individual translators, with the exception of one poem (“Patchwork Quilt”) that Lida asked us to add (otherwise she did not comment on the contents, except to say how delighted she was). I suspect that the excellent quality of the translations and the overall pleasing shape of the book comes out of this shared creative satisfaction, the fact that everyone was following individual inspiration. Perhaps I should also add that we took our time and agreed on deadlines collectively–no one was rushed.

Eugene Ostashevsky: One aspect that F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry shares with Rymbu’s Life in Space, as well as with Yusupova’s collection, is that all three are bilingual. The bilingualism of the books means they are addressed to several audiences at once–to poetry audiences in the US and UK (not at all the same audience), as well as to English-speakers globally, because we, or at least I, aren’t writing for just American readers now. Being bilingual, the books are also addressed to Russians–to global Russians also, meaning to Russians outside of Russia, to people fluent in Russian, and to people just beginning to learn Russian. I ended the introduction to Life in Space with a request that readers who don’t read Russian at least learn the letters so that they can pick up some of the materiality of the language on the facing page. It’s not because I have a Russian fetish, it’s because I think poems are material things, and especially material in the original. Just reading the translation is not enough for me. But I digressed and said nothing about the differences between the books, only the similarities. Sorry.

PL: Though Russian is the common language from which these poems originated, most of the poets have lived experiences in a number of cultural and linguistic contexts. Having grown up in Petrozavodsk, Karelia, Lida Yusupova lived in St. Petersburg and Jerusalem, and currently divides her time between Canada and Belize. Galina Rymbu was born in Omsk, Siberia, and Oksana Vasyakina further East, in Ust-Ilimsk, Irkutsk oblast. Lolita Agamalova was born in Chechnya and Egana Dzhabbarova spent her childhood in Georgia and currently lives in Yekaterinburg. What do you think these complex mobilities contribute to their poetics?

Ainsley Morse: In Yusupova’s case, I would say complex mobility makes her poetics. A lot of the poems in her 2013 book Ritual C-4 (excerpts from which open The Scar We Know) are outright multilingual and/or strongly gesturing toward other cultures, histories, languages, etc. This is a really interesting problem for translation, since part of what makes these poems powerful and strange is the simple fact that they tell these stories in Russian, and Yusupova–as someone who spent several decades living in Russia–is fully aware of how dramatically different these (Belizean, Canadian, American, etc.) scenarios and names sound and mean when they are transplanted into Russian. To some extent she is playing around with exoticism in a way that can seem not entirely politically correct. But both in Ritual and in more recent work, she also uses the distance gained from her own personal displacement to look back to Russia (to her own past and the present day alike) from an estranged position. I think this crucial shift in viewpoint is one of the moves that made Lida’s work so inspiring for some of the younger poets in the anthology.

Eugene Ostashevsky: It makes them modern. Modernity is displacement. But, on the less slogany level, it also shows that Russia is not just Moscow and Petersburg anymore, because Russia, with its history of absolutism, used to be like France–just Paris.

PL: Translators have played a very active role in bringing these books to English-language audiences. Some of the translators are themselves poets and activists, and many were born in the Soviet Union or to USSR-born parents. Considering that poetry translation is the act of co-creation in the new language, what do you think these complex identities of the translators contribute to the shape of these books?

Ainsley Morse: I have to say that I still don’t know very much about the personal background of the translators who did the bulk of the work on the Yusupova book–Madeline Kinkel and Hilah Kohen. I know that they’re both younger than me (by how much, I don’t know), hard-working, bright, responsive, creative and generous, and driven by a vested interest in the work.

With the anthology, I do remember feeling that we needed to involve younger translators–many of the poets there were born in the 1990s, and it seemed important to me that the English come from people reasonably coeval with them. But that was an easy task because there are so many fantastic young(er) Ru-En translators out there right now! I suppose that does bring the conversation back around to the question of family background, since for some of the translators growing up with Russian in the family probably means they achieved a greater degree of bilingual fluency at a younger age (without years of study). But we also worked with several marvelous translators who have just learned Russian from scratch.

The question of translators-cum-activists is interesting. In some ways the history of twentieth-century Ru-En translation is one of activism, since the Cold War narrative of oppressed writers drove much Russian literature publishing for a long time. To some extent this anthology will draw attention precisely because of the persistence of the Cold War model: Russia’s government is still/again villainous, and some of these poems call direct attention to this fact. In the internet age, though, translators have an easier time finding writers they find compelling for whatever reason–they don’t just automatically translate prominent dissidents and Nobel Prize winners. Also, although many of the translators whose work is featured in these books identify as queer, the problems that are relevant for queer poets in the US right now are not necessarily the same ones being grappled with in Russia. So it’s probably more important that the translator has a connection with the poems than necessarily with the poet / the poet’s self-identification.

Eugene Ostashevsky: Since translation is, at bottom, work with language, before you get to gender, ethnic or other identities, the translator needs to know how to write in the target language and how to read in the source language. The translator also needs self-control–you need to check even things you think you understand and you need to make sure you are not smothering the text with your own ideas. Having said that, it is also important–in fact, it’s crucial–for the translator to have an internal connection with the author. This can happen on any level. It can happen on the more existential level of shared, say, gender or sexual preference, although this kind of internal connection strikes me as impossibly broad if unsupported by others.

I personally need a connection through poetics. I really wanted to translate Lolita Agamalova’s Dilige, et quod vis fac, although it’s a lesbian sex poem, and I’m neither young nor a lesbian. But I also know what it’s like to use philosophy, even Neoplatonic philosophy, to talk about sex, I am at home in the kind of metaphysical poetry that she writes. And my job is not to imitate what she, as a character, is doing with another character, but to imitate in English what she, as a poet, is doing with the Russian language. We did aim for a range of “complex identities” of translators in our anthology but I don’t know to what extent that shows up on the page. Like, my “complex identity” is probably differently complex from the “complex identity” of Alex Karsavin, who is a terrific translator I first met working on this book–inventive, thoughtful, precise–but can you read the difference in our word choice? Translation is not the same as original poetry. It’s not about the translator, or rather it’s about the translator very, very obliquely. So identities don’t work in the same way.

PL: In the anglophone world, we have seen a growing interest on the part of translators and editors to give space to Russian queer and female writers. In 2019, for instance, Brooklyn Rail’s InTranslation folio “Life Stories, Death Sentences,” was co-edited by Anne O. Fisher and Margarita Meklina. This increased interest came on the wings of the reportage about the socially regressive laws passed in Russia that decriminalize domestic violence and criminalize “gay propaganda” (conveniently loosely defined), and most notoriously the persecution of gay men in Chechnya. On the geopolitical scale, we’re seeing Russian leadership align itself with the socially conservative values maintained in the US by the political far-right, upholding patriarchy and heteronormativity. In the Russian context, many if not most of these authors have engaged in acts of dissent. What do you think of the potential for these books to also act as works of activism in the anglophone context by, for instance, helping to build socially progressive alliances?

Ainsley Morse: I don’t know how much activism these books are capable of bringing about in the anglophone context. I am very glad they are all bilingual, because I think they are definitely capable of sending small shock-waves out into the Russian-reading community–because many of these texts really are earth-shaking and unprecedented in Russian. But my sense is that many of the poems come across as much less shocking in English, where women in particular have been writing the body and sex, etc. for a while now. I’d make an exception for Yusupova’s cycle “Verdicts,” composed of found poems made using court documents she accessed on various Russian legal websites. Several of these are extremely graphic and brutal, in English just as much as in Russian. But I worry too that the English-language poetry reading public has this special category for “brutal Eastern European art” and there’s a kind of automatic distancing that neatly sections off the visceral violence and pain there as the sort of thing that happens elsewhere. Ironically, I think the more programmatic work, which highlights the legal and social differences between the US and Russia, can be less effective at bridging that gap. That said, I recently taught Vasyakina’s “These People Didn’t Know my Father” to a class of non-Russian-speaking students and several people really responded–not as much to the narrator’s fantasies of an underground feminist-terrorist organization, but to her nuanced portrait of economic disparities and social-medical stigma. The “feminist poets” in the anthology are really addressing so much in their work–their “feminism” is often so far-reaching in its calls for human rights and general decency, it almost seems limiting to use that designation (even as we can see the crucial importance of specific demands for women’s rights).

Eugene Ostashevsky: Especially now, given Russian interference in elections in the US, the EU, and elsewhere, and given international cooperation among extreme-right-wing parties and the Russians, the enemy seems to be the same in many locations all over the world, and the systems seem increasingly similar. But that may be an optical illusion. Let me think about it. Well, Russia is just more patriarchal than the US, because the Russian state depends on the traumatization of men–of all of its male citizens–during army service, as well as by the casual violence of the family, of the street. Being a Russian man–a “common,” “normal” Russian man–has to do with the internalization of violence directed at you, with directing violence at others, with accepting it as the natural economy of manhood. I think in the US, which does not have the draft, but does have gun ownership, there exists systematic abuse of men in order to rule them, but it’s directed at a smaller subset of men and it’s organized differently. Just think of American prisons and of the likelihood that an African-American man will go to prison, as opposed to a representative of another group. But it’s less obvious how it works in the US, because oppression in the US tends to be by the indirect, alienated violence of money, rather than by simple beatings or shootings. I understand about police brutality, but there is also money brutality, and I hope I am not downplaying real physical violence if I say that money brutality is more in charge. Anyway, I don’t live in Russia and I don’t even live in the US now, and I’m not a sociologist, so my pontificating is not to be taken too seriously. What I was trying to get at is the obvious point–well, obvious to you and me but clearly not for everybody–that feminism and queerness are extremely good for “straight” men also, because these ideologies aim at constructing a different body politic, one where the men also would not be brutalized, where the state would not depend on the brutalization of men, and of others by means of men, to survive. As it does in Russia. As it does in part in the US, although the violence of money is so much more complicated and less clear cut, and maybe to some extent compatible with nonpatriarchal thinking. Maybe. I don’t know.

But I didn’t answer your question. Do I think these books can act as a work of resistance in an anglophone context? No doubt. I never say “no doubt,” but this is really no doubt. Much of the material in all three books translates pragmatically as well as semantically.

PL: In the process of translating and editing these books, what images, concepts, and/or words have emerged as some of the trickiest to carry over into English?

Ainsley Morse: Encroaching multilingualism! I talked about this some in relation to Yusupova above; her poems have words from English, Spanish, Kriol (in one poem, Inuktitut), as well as a persistent orientation toward a kind of “other” or foreign space (even when they’re written in plain Russian). Likewise some of the anthology poets use foreign words or phrases, and it’s always so hard to get–and then convey–a sense of how that feels and means in Russian (especially since the “other” language is so often English).

The legal language in Yusupova’s “Verdicts” cycle also offered a technically tricky problem. We, non-lawyers, were not familiar with this kind of language in English, and the Russian legal code is just different. In one case we had to redo a significant chunk because Lida pointed out that there isn’t a manslaughter charge (this had been our approximation of what was, crucially, “causing death by negligence”). Even “Verdicts” should technically be “Rulings,” but we went for the etymological rhyme (the root of the Russian word, Prigovory, is speaking or saying, di(c)t-).

For me, the “Verdicts” cycle also entailed a different kind of difficulty because of the extremely brutal and graphic violence toward women and LGBT+ people depicted in most of the poems. I should acknowledge right away that Madeline Kinkel is the translator of the cycle, for which I’m very grateful–I always knew they would need to be a big part of the book, but was reticent to translate them myself because simply reading them was such a viscerally wrenching experience. Since translating entails getting deep inside of texts and reading them over and over again, translating the “Verdicts” was sure to be hard going (of course, as editor of the book, I ended up working closely with them anyway). I remember Bela Shayevich told me that while she was translating Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time, which abounds in tales of relentless and horrific suffering, she would cry pretty much every day.

Eugene Ostashevsky: Relatively speaking, this is not hard material to translate. Older poetry is much harder, both because of greater linguistic materiality, especially in the case of classical forms, and because of greater conceptual dissimilarity. With contemporary Russian feminist poetry, though, we all live more or less in the same world, or at least we live in a world whose parts are kind of legible from the vantage point of other parts. Maybe the hardest part of the anthology was the title. F-pis’mo really translates as F-Writing, referring to écriture feminine, but to translate it as F-Writing into English would be like living in the 70s all over again, because the idea of poetry as écriture, which appeared in Russia only recently, becomes a key idea in experimental poetry in the US with Language poetry. So I translated F-pis’mo materially, because pis’mo originally means letter, the kind you send, but if you combine it with F, its meaning alters once again, to letter like ABC. So the title became F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry. The F is actually a Russian F, Ф, because it’s a what’s-the-f-you-lookin-at letter, and there’s even an obsolete expression, стоять фертом, to stand like an Ф, which is to have your elbows out and your hands by your waist, but figuratively it means to stand in a what’s-the-f-you-lookin-at pose. It’ll be a tiny book with an Ф on the cover. This kind of translation may be called a double sdvig.

Ainsley Morse translates from Russian and Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian and teaches at Dartmouth College. In addition to F Letter and The Scar We Know, she has worked mostly on Soviet-era poetry, prose and theory, including Vsevolod Nekrasov’s I Live I See and Igor Kholin’s Kholin 66: Diaries and Poems (both with Bela Shayevich, published by Ugly Duckling Presse), Andrei Egunov-Nikolev’s Beyond Tula: A Soviet Pastoral and Yuri Tynianov’s Permanent Evolution: Selected Essays on Literature, Theory and Film (with Philip Redko, published by Academic Studies Press).

Eugene Ostashevsky‘s books of poetry include The Pirate Who Does Not Know the Value of Pi (NYRB 2017), wonderfully translated into the language of German by Uljana Wolf and Monika Rinck, and into the language of music by Lucia Ronchetti, and The Life and Opinions of DJ Spinoza (UDP 2008), now available in digital copy here. As translator from Russian, he works primarily with OBERIU, the 1920s-1930s underground circle led by Daniil Kharms and Alexander Vvedensky. He has edited the first English-language collection of their writings, called OBERIU: An Anthology of Russian Absurdism (Northwestern UP, 2006). His collection of Alexander Vvedensky’s poetry, An Invitation for Me to Think (NYRB Poets, 2013), with contributions by Matvei Yankelevich, won the 2014 National Translation Award from the American Literary Translators Association. He is “against translation.”

Book Love: Julia Voznesenskaya’s The Women’s Decameron

(This blog post had to happen sometime.)

Sure, we’ve all fallen in love with people, but some of us have also fallen in love with books. I was in my early twenties, living in a newly post-Soviet Moscow, where I’d gone to work after college. Censorship had collapsed along with the Soviet Union, and many types of previously banned literature were flooding the Russian market. Tables with piles of books for sale were regular features outside many of the city’s metro stations. They were an incongruous mix of serious fiction by the likes of Bulgakov and Solzhenitsyn, self-help manuals, erotica of dubious provenance, and Russian translations of detective novels by James Hadley Chase. I don’t have an exact memory, but given that a good number of my books from that period were purchased off such tables, it is highly likely that this is where I found a novel titled Zhenskii Dekameron — The Women’s Decameron (transl. W.B. Linton, publ. Atlantic Monthly Press; other editions in Russian and English exist). Without a doubt, the fact that the word zhenskii was in the title was a major selling point. It was by a writer named Julia Voznesenskaya (here and elsewhere, I am using the spelling of authors’ names as they appear on their English translations, but given my willingness to die on the hill of Library of Congress transliteration, I am absolutely cringing inside). I’d never heard of her. She changed my life.

Voznesenskaya wrote The Women’s Decameron in 1985 while in exile in what was then West Germany. Many writers were expelled from the Soviet Union, but what makes her case highly unusual was that it was due to feminist activity. She came to feminism via her involvement in the dissident movement in the 1970s, for which she was arrested and imprisoned. Although she wasn’t initially interested in women’s issues, time in all-women’s camps and prisons changed her mind. She and three other women founded the Soviet feminist movement (it was tiny, but still a thing); they formed a women’s club and put out journals of women’s writing, for which they were hounded by the KGB and made to leave. Three of the four founders, including Voznesenskaya, were religious, and their views resembled Russian Orthodox teachings more than feminist theory, but The Women’s Decameron bears little trace of this. In the West, they broke up over their religious-secular divide, but not before being interviewed by Ms. Magazine. In the process of editing this post, Olga found a Calvert Journal article about the exhibition Leningrad Feminism 1979, devoted to this Soviet feminist collective; it was shown in St. Petersburg earlier this year, and once COVID-19 conditions allow, will move to Moscow and then to locations in Western Europe. Thank you so much, Olga, for this amazing, and unexpected find — hopefully, this exhibition is a start to making these Soviet feminists better known in both Russia and the West. Voznesenskaya herself won’t know about it: she died in Berlin in 2015. There’s a good chance, though, that she wouldn’t want anything to do with it. After emigration, she wrote detective novels, but then spent some time in a French monastery, whereby she renounced her previous works and turned to writing Russian Orthodox fantasy (don’t ask; I don’t know).

The Women’s Decameron is Voznesenskaya’s first, and best-known work, although in this case, “best-known” is a relative term (I was surprised and overjoyed when several people on Twitter responded to my, um, numerous posts saying they’d read it, although given all the brilliant Russian literature people on Twitter, I shouldn’t have been surprised). Because Voznesenskaya was exiled, The Women’s Decameron was not published in the Soviet Union; when it became available in post-Soviet Russia, it went seemingly unnoticed. She may be most familiar in Slavic academia in the West, and even then, not so much.

My poor love deserves better. A reworking of Boccaccio’s Decameron from a female point of view, the novel features ten women of different backgrounds and life experiences quarantined together after giving birth in a late Soviet-era maternity ward because of a spreading infection (if nothing else, read it for the unintentional parallel with our current situation, although I promise you, there’s much more to it than that). They pass the time telling stories about their lives and those of their friends and families in ten chapters containing each of their ten stories, with an author-narrator who opens and closes the pieces. Each chapter is devoted to a different theme; when I teach this novel in my course Writing the Body in Contemporary Russian Women’s Fiction, we read “First Love,” “Sex in Farcical Situations,” “Rapists and their Victims,” and “Happiness.” Love and happiness (or, rather, a distinct lack thereof) are common themes in Russian literature; but the two other titles, and the all-female space of this novel, signal that The Women’s Decameron is a different type of book.

Russian literature has no shortage of women writers and female protagonists. But as Barbara Heldt notes in Terrible Perfection: Women and Russian Literature, which I could cite directly if it weren’t for the pandemic-induced closure of our university library, what is considered the Russian canon is overwhelmingly made up of male writers and male protagonists. Female protagonists, while crucial to the plot, are usually complements to their male counterparts, and their own development is rarely shown. Other scholars have pointed out Russian literature’s puritanical approach to the body and sexuality, which were not considered appropriate subjects for “high” literature. Once in a while, male characters got to be physical, but women rarely did, and one was thrown under a train for trying.

This changed in the liberalized atmosphere of glasnost’ and the early post-Soviet period, which witnessed an explosion of women’s voices. In defiance of Russian and Soviet patriarchy and puritanism, writers such as Svetlana Vasilenko, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, Valeria Narbikova, and Marina Palei, among many others, created a female-centered space in Russian literature, with women protagonists who were both intellectual and physical beings. Their works, often explicitly concerned with the act of writing, were characterized by a palpable presence of female bodies in various manifestations: sex, violence, pregnancy, abortion, disease, etc. While none of them had read French feminist theory, and several openly eschewed any association with feminism, they were, in Hélène Cixous’s formulation, writing the body. In Slavic Studies in the West, these writers, who do not form a coherent whole but have enough in common to be talked about together, became known as New Women’s Prose, first and foremost due to the pioneering efforts of Helena Goscilo, in such publications as Dehexing Sex: Russian Womanhood During and After Glasnost (having relied on it extensively in my dissertation, this one I have on my shelves).

The few scholars who have written on Voznesenskaya place her in the general category of Soviet women’s literature, while those who write on New Women’s Prose don’t include her. This is understandable, since living in West Germany, she had no connections with the other Russian women writers. But the striking similarity is that Voznesenskaya also writes the body: The Women’s Decameron centers women’s narratives of sexuality, violation, etc. It’s a pretty convincing argument, if I do say so myself (I did say so myself, in my dissertation and in the article I wrote about The Women’s Decameron).

An account of sex on the roof due to a lack of privacy in an acute Soviet housing shortage – that’s in there. The story about appearing in front of a theater audience in bed with your lover due to the mechanism of an inopportunely revolving stage — that’s in there too, as is a romp with an American “spy” on top of the heads of three KGB agents hiding under the bed during a room search gone awry. Also in there are the more somber stories of child sexual abuse and the many instances of rape, some of which the women verbalize for the first time to each other. Powerless to stop being raped in life, they support each other and try to heal themselves through telling their stories. And in one instance, they, and we, are overcome by unadulterated hilarity and gratitude because a character was able to get highly painful revenge on her would-be attacker with a pair of imported mittens. Female bodies, both their pleasures and pains, are very much written here.

Admittedly, in a novel that consciously tries to represent a spectrum of women’s experiences, making them all mothers is a regressive move. That said, Voznesenskaya goes against convention in allowing motherhood to coexist with sexuality (take that, Tolstoy), and notably, the characters bond over a range of topics, not motherhood itself. Indeed, she espouses several ideas that make her ahead of her time. She openly terms one protagonist a feminist, which, let’s just say isn’t something one expects from late Soviet-era works (or, really, many other eras). There is also a recognition that other types of oppression intersect with gender: several protagonists’ lives are shaped by their economic standing, whereas another’s is by being Jewish, the latter also indicative of Voznesenskaya’s rejection of Soviet anti-Semitism. A storyline about one of the protagonists’ love interests mentions racism toward those from the Caucasus. There’s more to say about what else The Women’s Decameron does, including revealing aspects of Soviet life that the regime tried to silence, but that would require another post.

When I say Voznesenskaya changed my life, partially I mean that she largely determined my academic path, handing me my dissertation topic and leading me to discover the other contemporary women writers, whom I teach and have written on. More fundamentally, I mean that The Women’s Decameron was my first time reading a Russian work that gave voice to viscerally honest, specifically female experiences. Over the years, I’d had lots of amazing conversations with Russian books, but this was the first one that spoke back in a shared language. In the women writers course, my students really respond to this novel. Some of them say about all the writers that they didn’t know there was Russian literature like this. I didn’t either, until Voznesenskaya, and through her several others, showed me that there could be.

Below is the opening of The Women’s Decameron. The right-hand image underneath that shows the never-to-be-detached Post-it notes from graduate school. Although this novel is, sadly, out of print, the English translation is still available here and, as much as I don’t want to recommend a particular mail-order giant, here. In Russian, it seems to be available here and online here (although I have no personal knowledge of either of those sites). Try it. Who knows; you might fall in love, too.

The Women’s Decameron by Julia Voznesenskaya

“How is it possible to read in this bedlam!” thought Emma. She turned over on to her stomach, propped the Decameron between her elbows, pulled the pillow over her ears and tried to concentrate.

She could already visualize how the play would begin. As they entered the auditorium and spectators would not be met by the usual theatre attendants, but by monks with their cowls drawn down over their eyes; they would check the tickets and show the spectators to their seats in the dark auditorium, lighting the way and pointing out the seat numbers, with old-fashioned lanterns. She would have to call in at the Hermitage, look out a suitable lantern, and draw a sketch of it … The stage would be open from the very beginning, but lit only by a bluish moon. It would depict a square in Florence with the dark outlines of a fountain and a church door, over which would be the inscription “Memento Mori” – remember you must die. Every now and then some monks would cross the stage with a cart – the corpse collectors. And a bell, there must definitely be a bell ringing the whole time – “For whom the bell tolls.” It was essential that from the very beginning, even before the play started, there should be a feeling of death in the theatre. Against this background ten merry mortals would tell their stories.

Yet it was difficult to believe that it happened like that: plague, death and misery were all around and in the midst of this a company of cavaliers and ladies were amusing each other with romantic and bawdy stories. These women; on the other hand, did not have the plague but a simple skin infection such as frequently occurs in maternity hospitals, and yet look at all the tears and hysterics! Perhaps people were much shallower nowadays. Stupid women, why were they so impatient? Were they in such a hurry to

start the nappy-changing routine? God, the very thought was enough to make you want to give up: thirty liners, thirty nappies and as many swaddling sheets, rain or shine. And each one had to be washed, boiled and ironed on both sides. It could drive you crazy. In the West they had invented disposable nappies and plastic pants long ago. Our people were supposed to be involved in industrial espionage, so why couldn’t they steal some useful secret instead of always going for electronics?

“Hey, girls! You could at least take it in turns to whine! The noise is really bugging me. If my milk goes off I’ll really freak out!” This outburst came from Zina, a “woman of no fixed abode” as the doctors described her on their rounds; in other words, a tramp. Nobody came to visit her, and she was in no hurry to leave the hospital.

“If only we had something nice to think about!” sighed Irina, or Irishka as everyone called her, a plump girl who was popular in the ward because of her kind, homely disposition.

And then it suddenly dawned on Emma. She lifted the Decameron high above her head so that everyone could see the fat book in its colourful cover. “Dear mothers! How many of you have read this book? “Naturally about half of them had. “Well,” continued Emma, “for those who haven’t I’ll explain it simply. During a plague ten young men and women leave the city and place themselves in quarantine for ten days, just as they’ve done to us here. Each day they take it in turns to tell each other different stories about life and love, the tricks that clever lovers play and the tragedies that come from love. How about all of us doing the same?”

That was all they needed. They immediately decided that this was much more interesting than telling endless stories about family problems.

Making People Feel Uneasy: Joanna Chen in Conversation with Katherine Young

Katherine Young, a poet and translator, gave this interview on BLARB, the blog of the esteemed Los Angeles Review of Books. In 2018, Academic Studies Press published Young’s translation of the trilogy, Farewell, Aylis, by Akram Aylisli, currently a political prisoner in his native Azerbaijan (Young has spearheaded efforts to free him, including a recent petition circulated on social media). Olga Zilberbourg reviewed this novel, which Punctured Lines noted in our post. As we also noted, an excerpt from his novella, A Fantastical Traffic Jam, translated by Young, can be found here.

Young’s latest project is the translation of Look at Him by Anna Starobinets (Slavica, forthcoming 2020), an open, unflinching account of her abortion that was controversial when it came out in Russia. As Young says, “Women don’t talk about these things, even with their partners, so to write a book in which you expose the most intimate details of your body and the choices you made medically is a violation of a lot of subtle taboos about women who are supposed to grin and bear their trials and tribulations.”

Young also talks about being a poet and how much Russian poetry has shaped her own: “I feel very much more informed by Russian poets than most American poets. I’ve read Walt Whitman, but I don’t identify with him the same way I might say Alexander Pushkin or Mikhail Lermontov or Anna Akhmatova.”

You can read the full interview here: https://blog.lareviewofbooks.org/interviews/making-people-feel-uneasy-joanna-chen-conversation-katherine-young/

Q&A with Lea Zeltserman: Looking at Soviet-Jewish Immigration through Soviet-Jewish Food

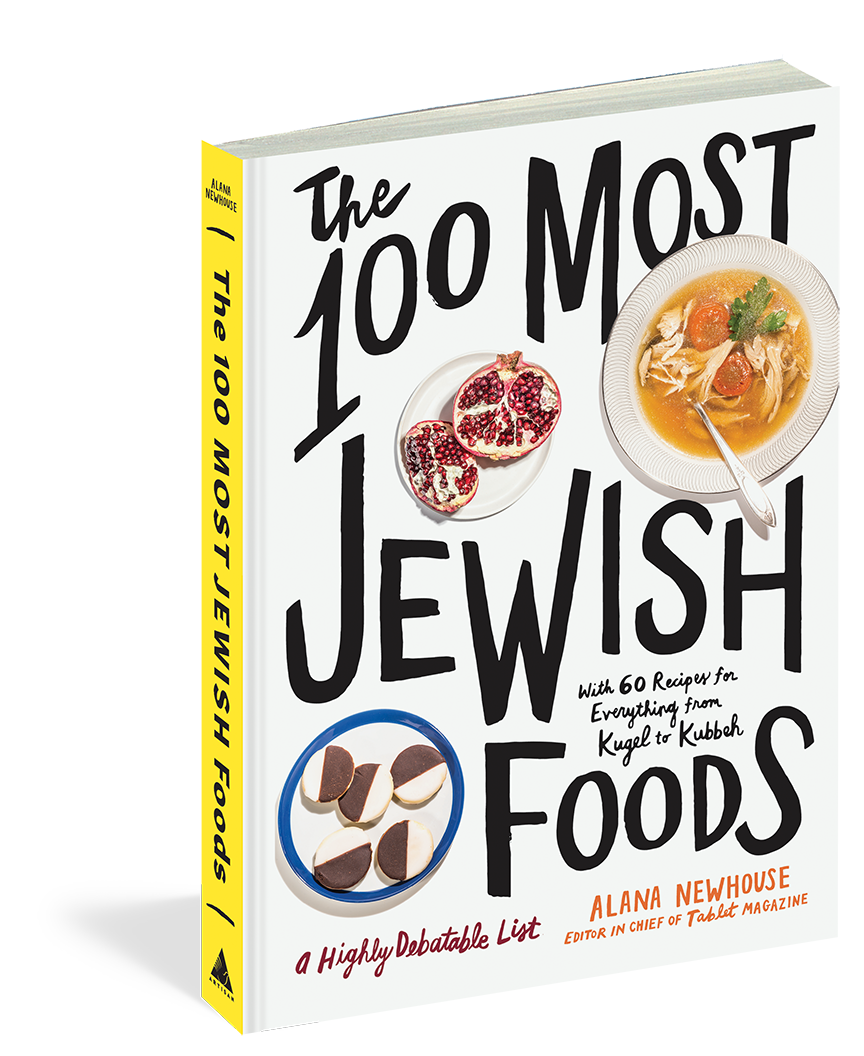

Today Punctured Lines features a Q&A with Lea Zeltserman, a Toronto-based writer focusing on, among other things, Soviet-Jewish immigration and food. Lea is a contributor to The 100 Most Jewish Foods: A Highly Debatable List (Artisan, 2019) with her piece “The Secrets of Soviet Cuisine.” Her two most recent food-related pieces are “TweetYourShabbat is all about embracing diverse – and imperfect – Shabbat dinners” and “Where the Russian Grocery Store Means Abundance,” whereas her “Announcing the Soviet-Jewish Decade: A 2010s Top 10” is a round-up of books, plus a documentary and an album, about Soviet-Jewish culture. Lea answered our questions by email.

Punctured Lines: You publish a newsletter, The Soviet Samovar, “a monthly round-up of Russian-Jewish news, events and culture,” with the emphasis on (ex-)Soviet Jews in the North American diaspora. What motivated you to start this project? What audience(s) is it aimed at and what do you hope they get out of it?

Lea Zeltserman: When I first started writing about Russian-Jewish issues, there was nothing out there. We were all just starting to get online, starting to come into ourselves as a community. I was excited each time I saw an article about Russian Jews in the media, and I simultaneously realized that there are many things we ourselves don’t know about our history. The Soviet Samovar was a way to bring that together. By now, there’s so much great work coming out of the Russian-Jewish world that I can be more selective. It’s shifted into a more literary, culture and book-focused round-up.

A lot of my work is for broader North American audiences, but the newsletter is aimed at Russian Jews. Though of course everyone should subscribe! The content is for everyone, and articles featured are often published in mainstream publications. But when I’m writing my commentary, there’s a distinct sense of “we, Russian Jews and our experiences, and here’s what we think about the world and our place in it.” I don’t tiptoe around, or hold back if I think something is damaging to our community. Which is not to suggest that it’s a monthly rant. Not even close. There is lots of thoughtful, smart, insightful writing out there, which I’m always excited to feature. There’s much to be proud of in our accomplishments, and The Soviet Samovar is a way to bring that together, draw attention to one another, and hopefully, give us all something to think about – about our history and the people and events that shaped us.

PL: You write a lot about Soviet-Jewish food, specifically how it reflects Soviet-Jewish culture and history. As you say in your essay for Tablet Magazine, “Defining Soviet Jewish Cuisine,” “For most Jews, the first bite of pork is a transgressive, often formative, moment. But for Soviet Jews, pork-laden sosiski [PL: wieners/hot dogs] were an everyday food.” Why the focus on food – what can looking at what Soviet Jews ate and continue to eat tell us more broadly about Soviet-Jewish life, both in the former Soviet countries and in the diaspora?

LZ: I’ve always been interested in food. When Tablet published their “100 Jewish Foods” feature online, I was surprised to see everyday Russian food on the list (borsch, cabbage rolls, rye bread, pickles, herring) associated instead with “Old World Russia.” This food might be “Old World” for many Jews whose Russianness lies several generations in the past, but for us, this is the food we grew up on. It’s our “now food.” This oversight is symbolic of the frozen-in-time understanding of Russian Jewry that habitually ignores the existence of the contemporary Russian-Jewish community. That really bothered me. So I wrote them, and they were great and very interested, and my article came out of that (and then was included in the 100 Jewish Foods book).

The sosiski, of course. They’re such a powerful image for Jews. For Russian Jews they’re real and nostalgic, and for North American Jews, they were something that was used dismissively toward Russian Jews to question our legitimacy. So yes, you start with jokes about sosiski and suddenly, there’s a whole story about who we are and what we overcame, why we stopped keeping kosher but still felt so strongly about our Jewish identity. And that happens over and over – you ask a few questions about our food and, because everything was so centralized and controlled, entire historical episodes, Jewish and not, come tumbling out.

Many Russian Jews don’t reflect on our food either. I’ve been so touched by the reactions to my writing and my talks on the subject. People really respond to hearing that this everyday “stuff” matters. That what their mothers and grandmothers do (or did) is relevant and weighty, and has significance to Jewish history and Jewish lives. Our dishes get at the story of our lives in a different way, especially for Soviet families, where getting and preparing food was such a major part of daily routine, never mind bigger moments like war, famines, the Shoah.

I also think about it as a parent, and what I want my children to know of their heritage. Kugel, brisket, and knishes aren’t our recent history. I don’t want them thinking that’s their food, or wondering why their food isn’t legitimately Jewish. Our stock list of Jewish food needs a shaking up and I strongly believe that our Soviet-era food, from all the republics, has a rightful place on that list. As for why are we still eating it? That’s something I’m still exploring, that intimate relationship between comfort and familiarity, how it fits into immigration and being refugees, all mixed up with the worst parts of the USSR. It reflects all the complexity and contradictions of our heritage, which we, quite literally, fill our bellies with every day. It’s part of our identity. It would be a betrayal to sweep it away and replace it with knishes and bagels (well, maybe the bagels).

Food is a little scrap of the past that I can touch and taste. I’ll never hear the sounds of the train station from which my paternal grandmother escaped the coming Nazis when she evacuated from Zhitomir. But a pot of soup, I can make an attempt at.

PL: The discussion of Soviet-Jewish pork consumption brings up something else you’ve written about, namely, the often stark differences between (ex-)Soviet and North American Jews. These differences exist not only in terms of food, but more generally: as you point out, they manifest themselves in terms of attitudes toward Soviet-Jewish immigration (“Why Russian Jews Don’t Want to Hear About Being Saved”), experiences of the Holocaust (“On #FirstSurvivor and the Russian-Jewish Holocaust experience”), and more playfully, treasured customs like New Year trees (“O Yolka Tree, O Yolka Tree”). Can you talk about what you see as the main differences between the two communities and also what, if anything, can be done to bring them closer together – or whether this is necessary?

LZ: Hmm, that’s a great question. And an unexpectedly difficult one. I’m going to start with the second question. Which is that, I don’t know anymore what will “work.” As time passes, we naturally become more integrated. Even myself, as an example – I grew up in the mainstream Canadian Jewish community, but always feeling like an outsider. My kids will feel less that way, I imagine. There are more writers now in Jewish media who straddle both worlds and bring a Soviet perspective as the norm – look at someone like Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt at the Forward. But, I still get comments about going back where I came from in response to my work. There are still separate Limmud conferences, as one major example of communal non-integration. If you go to Jewish events, at least in Toronto, there’s rarely anything Russian/Soviet – you have to go to the Russian-Jewish events for that. That’s not always about exclusion though. Those types of communal spaces and events are important for Russian Jews too. It’s a space for us to talk among ourselves, to share experiences and find commonalities (and stop explaining ourselves). There are programs like the J-Academy camp in Toronto, which build Russian-Jewish culture and identity. There’s tremendous value in that separation, too.

On the flip side, there are great examples of “cross-cultural moments,” like Yiddish Glory, spearheaded by Anna Shternshis and Psoy Korolenko, which has been rightfully recognized all over the world and brought legitimacy to our experiences, especially in the Holocaust. (Yad Vashem has a special focus on the Holocaust on Soviet territories, for example; writers like Izabella Tabarovsky have done a lot of work in bringing that history to broader audiences.) I think that it’s partly because Yiddish Glory taps into the Holocaust and yiddishkeit and nostalgia. And to be clear, it’s an amazing project and I talk it up at every opportunity – I’m thrilled it’s received the acclaim it has. But I do think its popularity in the wider Jewish community is partially tied into the reasons above. Hopefully though, these types of projects will start to bridge that gap. It’s changing, but slowly.

There’s increasing interest in Soviet Jews and our experiences. My “Soviet-Jewish Decade” series generated strong interest from a Russian and non-Russian Jewish audience. At the same time, I still see frequent reminders that we’re not part of the mainstream. Minor things like headlines about “old world borsch,” as if we’re not eating that in the here and now. It’s disconcerting to see your everyday discussed as if it’s some relic left behind, belonging to impoverished shtetl immigrants. Other examples are more blatant and angering, but I don’t want to get into a list of outrages here. We remain an afterthought; not part of a broader understanding of what the Jewish community is. We don’t fit tidily into existing narratives of Jewishness. Occasionally, I’ll see a writer who isn’t a Russian Jew mention us as a matter of course in articles about the American-Jewish community. And standout examples like Rokhl Kafrissen, whose Tablet column on Yiddish culture and history regularly includes Soviet Jewry as a “normal” topic. I suspect that this feeling exists across other minority groups within the Jewish community too.

To the first part of your question, I think our differences are muting over time. But we’re still seen as an Other, someone to be remembered or included, but not a group that’s inherently part of the North American-Jewish world. And we’re still referenced as a means to an end, part of the narrative that the Soviet Jewry movement enabled US Jewry to grow, which, well, no one wants their suffering to be someone else’s stage of development. Anecdotally, I’ve talked to many Russian Jews who feel that they’re looked down upon and seen as inferior. Highly successful people in their careers and lives, and yet, this feeling persists. And culturally, there are genuine differences. Language, obviously. Food, history, family stories. Anekdoty [PL: jokes] – those never fully translate. Our fundamental definition of Jewish identity is still different, though that’s several articles in itself.

PL: As a writer one of whose major topics is Soviet-Jewish immigration, do you find yourself connecting with other diaspora writers?

LZ: Absolutely! I’m still amazed at finding all these people, and the many, many points of connection among our experiences. I never had that growing up. Though I mostly felt very Canadian, there were always gaps and differences that I tried to ignore – or often took as a sign there was something wrong with me or my family. I’m still exploring that and still finding a lot of meaning in those connections and the realization that my experiences weren’t alone.