It would be hard to overstate my love of both figure skating and detective fiction, which admittedly isn’t something one normally thinks of together. It is therefore beyond thrilling to feature this personal essay by Alina Adams, who has written a series of five figure skating murder mysteries (yes, really, and I plan to order every one of them). A prolific writer with several fiction and non-fiction titles, Alina’s most recent novel is The Nesting Dolls, which you can read about in the poignant and humor-filled conversation between her and Maria Kuznetsova that Olga recently organized on this blog. I loved reading the story Alina tells below about working as a Russian-speaking figure skating researcher (she must have had a hand in many of the broadcasts that I avidly watched), and I confess to losing, in the best possible way, some of my time to being nostalgically taken back to 1990s figure skating coverage through the two videos in the piece, one of which features Alina translating (for Irina Slutskaya! You all know who she is, right?! Right?!). Let yourself be transported to that marvelous skating era, get ready for all the figure skating at the Olympics next month . . . and watch out, there’s a murderer, or five, on the loose.

You Never Know When Speaking Russian Might Come in Handy…:

An Essay by Alina Adams

I immigrated to the United States from Odessa, (then-) USSR in 1977. I was seven years old. I spoke no English, only Russian.

I was the sole Russian-speaker in my second grade class at Jewish Day School. When the other kids spoke to me in English, I responded in Russian. When the teacher gave us a writing assignment, I wrote it in Russian.

I was never, ever going to learn English!

And then I fell in love.

With television.

Television was where the happy children were. The ones who lived in a house with a big staircase to slide down, not an apartment where all the furniture looked exactly like the furniture of every other Russian-speaking family newly arrived in San Francisco (we assume Jewish Federation got a great deal on all the identical chairs, tables, and bedspreads). The ones who ate hamburgers instead of kotlety. The ones who drank bright red, cherry-flavored medicine with cartoon characters on the label when they had a cold instead of laying down to get banki applied to their backs, dry mustard applied to their front, and their feet dunked into boiling water.

I wanted to be like the happy children on television. So I learned English.

My parents still spoke to me in Russian. But what language I might deign to reply in was anybody’s guess.

My love for the happy children who lived inside the television extended to wanting to join them. Not as an actor. I knew I was too funny-looking for that. But I could be the person who wrote the words that the people inside the televisions said. That’s where the real power was.

And those words would be in English!

Who needed Russian?

Cut to: Me. Freshly out of college with a degree in Broadcast Communication Arts. And looking for a job.

Flashback: I have a younger brother. He was born in the United States. He was a competitive figure skater (1996 U.S. Open Novice Ice Dance Champion). My immigrant parents had better things to do — like, you know, earning a living — than drive him to daily practice or chaperone him at competitions. So that became my job.

I learned more about figure skating than I ever thought there was to know.

Which is why, when it came time to apply for a job as a researcher and writer with ABC Sports’ ice skating department, I knew quite a bit.

But, guess what — so did a lot of other people (many of them former skaters themselves).

Except those other people didn’t speak Russian.

And I did.

Suddenly, the language that once kept me from the happy people in the television was the one bringing me into it.

Thus began my years of traveling around the globe, from World Championships to international qualifiers to the 1998 Olympic Games in Nagano, Japan.

And back to the former USSR.

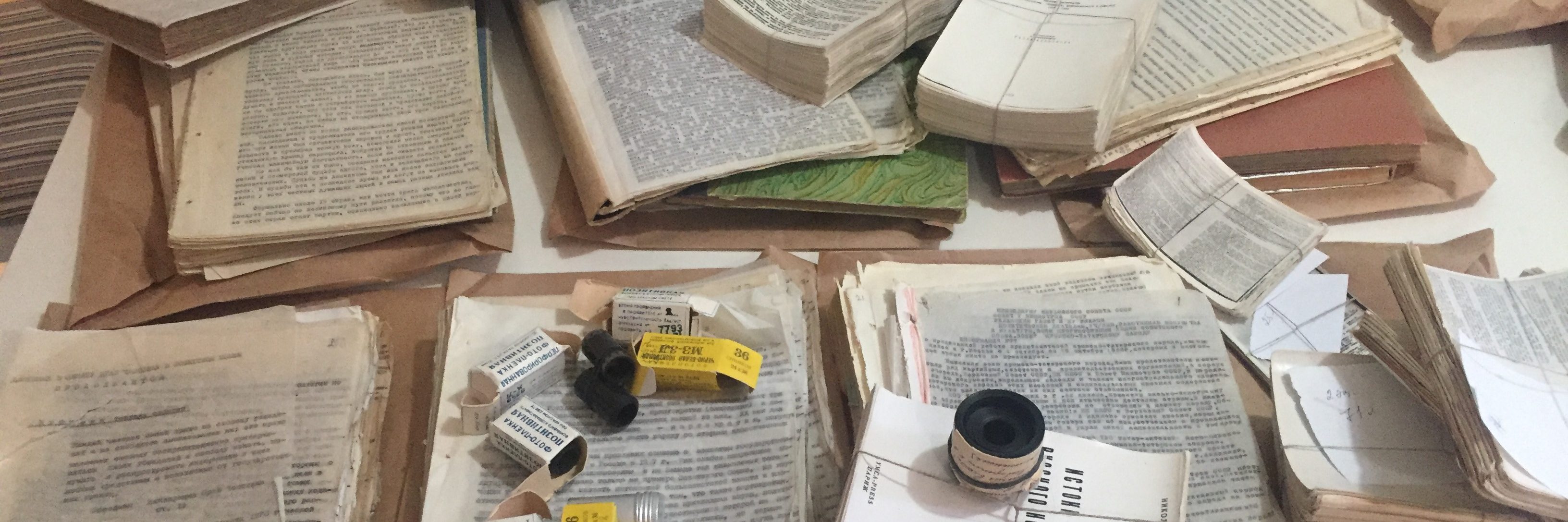

By the time I returned with an ABC crew to shoot profile features on the country’s top athletes, the Soviet Union had collapsed. It was Russia now. And Ukraine. And Belarus. And Armenia and three different Baltics and . . . (A fun game in the media truck was placing bets on which formerly Soviet skaters would declare themselves which ethnicity in order to ensure a place on the competitive team. For instance, the Ukrainian named Evgeni Plushenko and the Georgian-sounding Anton Sikharulidze competed for Russia, while the Russian-sounding Igor Pashkevitch represented Azerbaijan, as did Inga Rodionova. We’re not even counting Marina Anissina declaring herself French or Aljona Savchenko becoming German.)

My job as a skating researcher included interviewing the skaters and their coaches to get all those fun tidbits the announcers share on the air: “She began skating at the age of three because her grandmother called her a typhoon and needed to stop her from bouncing around their communal apartment!” or “He is the first athlete from Estonia to win a bronze medal at the European Championships since…” (What? You thought Dick Button and Peggy Fleming generated those fun factoids all on their own?)

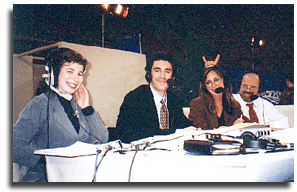

It also included visiting the skaters in their homes, interviewing them in Russian on camera, translating their replies and, once in a while, even dubbing their answers into Russian-accented English for the television profile. (You can listen to me doing two versions of the same accent, here. I am playing both Irina Slutskaya and her mother. If you scroll through to the end, you can see me translating her championship interview live on the air, too. On a different note, about six minutes into this video is a profile of Misha Shmerkin, a former fellow Odessa resident now representing Israel. Though you can’t hear me in the piece, I’m the one who asked him all the questions that he is answering on camera.)

The experience was disquieting, to say the least. Not because I was forcing my brain to operate 24/7 in a language I had deliberately pushed to the back of my conscience for almost two decades (and had no one to check my stupidity if I screwed up; the English-speaking production staff assumed everything I told them was accurate). It was because, in returning to the former USSR and going from home to home, interviewing people my age and my parents’ age, I was being confronted with the life I might have lived.

Not as a competitive athlete. I didn’t have the talent or the drive for that. But as an ex-Soviet citizen, navigating a country that had collapsed around me, desperately trying to figure out what the new rules were while clinging to the old ones because they were the only ones I understood. I entered communal apartment after communal apartment. I ate the food they put out for us, understanding in a way my colleagues did not how hard it had been to get. I nodded as a skater’s mother whispered to me, “Don’t tell them my husband is Jewish,” and barely flinched when, while shooting inside a hospital for a piece on an injured skater, random cats wandered in and out of the wards.

I was getting a glimpse of the life I might have led if my parents hadn’t made the decision to emigrate in the 1970s, when no one had a clue that the empire had less than twenty years of life left in it, or that return visits would become commonplace. When my parents took the chance to leave, it was like jumping off the edge of the world into an abyss. Nobody knew what the West had to offer or how they might survive there. And everybody understood that there would be no going back. It might as well have been a one-way mission to Mars.

My trips to the former USSR were an ongoing exercise in, “There but for the grace of God, go I.”

But I remembered what I’d seen there, and when, in 2002, following the (latest) Olympic judging scandal an editor at Berkley Prime Crime asked me to write a series of figure skating murder mysteries, I jumped at the chance.

The chance to not only reveal all the behind-the-scenes gossip I couldn’t publish using skaters’ real names, but also to include the observations I’d made about life in the former USSR through the unique lens of elite athletes who’d survived the Soviet days and were now trying to make sense of the present. I could write about those who triumphed and those who slipped through the cracks. I could write about what was, and about who I might have been.

There are five books in the Figure Skating Mystery series. The third installment, Axel of Evil, takes place in Moscow and incorporates everything I saw, everything I heard, and everything I suspected when I worked there.

The first one, Murder on Ice, was based on the aformentioned 2002 Olympic judging scandal, where the Pairs judge was accused of favoring the Russian team over the Canadian one. In Murder on Ice, a judge is accused of giving the Ladies’ gold to Russia’s dour ice queen over America’s perky ice princess. And then the judge ends up dead (that didn’t happen in 2002). Who will investigate the crime? Why, none other than the trusty skating researcher! (Clearly, I subscribe to the policy of: Write What You Know.)

In Murder on Ice, I take all of the clichés that Americans have about Russians and (hopefully) turn them on their heads. In Axel of Evil, I continue that objective, but I do it by putting the American researcher, my heroine, Bex Levy, out of her element and onto Russian soil. Here, people are making as many assumptions about her as she is making about them. Clichés work both ways. In retrospect, I guess I was working out issues of being a Soviet-born American — whose life would have been very different had my family stayed in the USSR — by writing from the point of view of an American digging into the lives of those who left, as well as of those who stayed. I get to be both an insider and an outsider. I get to be the native and the other. I get to play the role of someone born in the US, and someone who grew up in the USSR. Because, in real life, I’ll always be somebody who is stuck in-between.

And I get to prove what my parents said all along. You never know when speaking Russian might come in handy . . . .

Alina Adams was born in Odessa, USSR and moved to the United States with her family in 1977. She has worked as a figure skating researcher, writer, and producer for ABC Sports, ESPN, NBC, and TNT. She is the author of Inside Figure Skating, Sarah Hughes: Skating To the Stars, and the figure skating mystery series consisting of Murder on Ice, On Thin Ice, Axel of Evil, Death Drop, and Skate Crime. Her historical fiction novel, The Nesting Dolls, traces three generations of a Soviet-Jewish family from Odessa to Brooklyn. Visit her website at: www.AlinaAdams.com

Figure skating mysteries! Now, that’s a genre I’ve not come across before!!! I’m intrigued…

LikeLiked by 3 people

Exactly! Feeds my love of both, which I never thought I’d see together.

LikeLiked by 2 people